News

#74 Objekt des Monats: “To the Clandestine Maternity Home" von Valente Ngwenya Malangatana

November 2024

© Foto Iwalewahaus

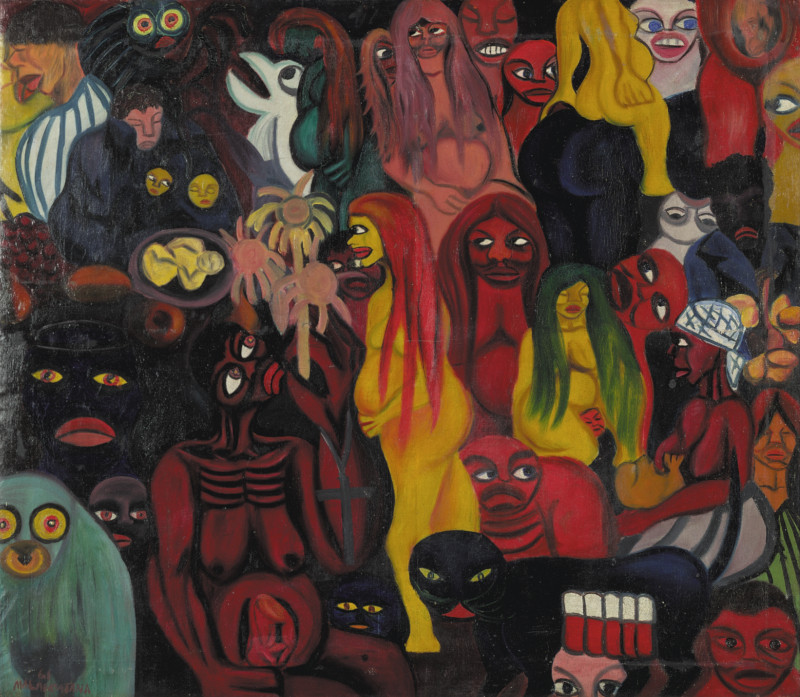

“To the Clandestine Maternity Home" von Valente Ngwenya Malangatana, Mosambik

1961. Öl auf Leinwand.

Half-an-hour with this painting ranked among my most life-changing experiences before an artwork. In the Iwalewahaus storeroom where I was privileged to see it, I had no alternative but to get up close. Malangatana’s range of palette, saturated colours and swirling brushwork were overwhelming. I tried to imagine the intentions which prompted him.

In 1961, this rural migrant to Mozambique’s capital (Lourenço Marques, now Maputo) was living in Sommerschielde, an exclusively European part of the city. His studio, where he also slept, was a garage belonging to the celebrated architect, “Pancho” Guedes. Guedes had offered him the space, with rent in paintings, eighteen months before. When making the deal, he forbade Malangatana to continue with formal art training at the capital’s Núcleo de Arte and sent him for six weeks to Matalana, his rural birthplace. According to Malangtana, Guedes insisted that he immerse himself in the so-called “traditional” culture of his people, the Rongas of southern Mozambique. Guedes and his European friends, including Ulli Beier, thought the resulting paintings, containing images which drew on Ronga history and culture, threw off the “pollution” of conventional western art1. Followers of Jung, they considered Malangatana’s so-called “untutored” works as dreamlike messages from the “heroic and universal unconscious” of humanity2.

However, I propose that in this example Malangatana drew on so-called “traditional” images to depict an all-too-real scene from the urban underworld of Lourenço Marques. In colonial times white South-Africans flocked to its beaches and nightclubs, because they were pick-up spots for interracial sex beyond the jurisdiction of apartheid. Malangatana witnessed their activities. He told me in interview that he learned English “on the beach”. The painting shows the nightmare consequences for its women victims. Arguably, we could view it through the agonised eyes of the woman in the lower-left centre, who resembles the self-portraits which Malangatana inserted in other works. Be that as it may, To the Clandestine Maternity Home expresses his abhorrence and denunciation of this aspect of colonialism. It thereby expresses the humanitarian sensibilities, in the words of Chika Okeke-Aguku, which “articulate the unpredictable outcomes of the postcolonial subject’s multiple religious, social and political worlds”3.

Dieses Objekt des Monats wurde bereits 2018 von Richard Gray, ein renommierter Kunsthistoriker und Kurator, bei seinem damaligen Forschungsaufenthalt ausgewählt. Zu der neuen Ausstellung hat er sozusagen ein zu seinem ursprünglichen Text geschrieben.

1 Malangatana, 2003. Tribute to Pancho Guedes in Viva Pancho!, ed Guedes & Guedes, p16. Total Cad Academy, Durban, http://www.guedes.info/vivapdf.htm, accessed 27/12/2018.

2 Miller, David, 1991. Primitive Art and the Necessity of Primitivism to Art. In Hillier (ed) The Myth of Primitivism: perspectives on art, p56. Routledge.

3 Okeke-Aguku, Chika, 2015. Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (p162). Durham: Duke UP. To be historically accurate, Mozambique won independence in 1975, so, in 1961, Malangatana was not yet a post-colonial subject”. Okeke-Aguku’s insight nonetheless remains of value.